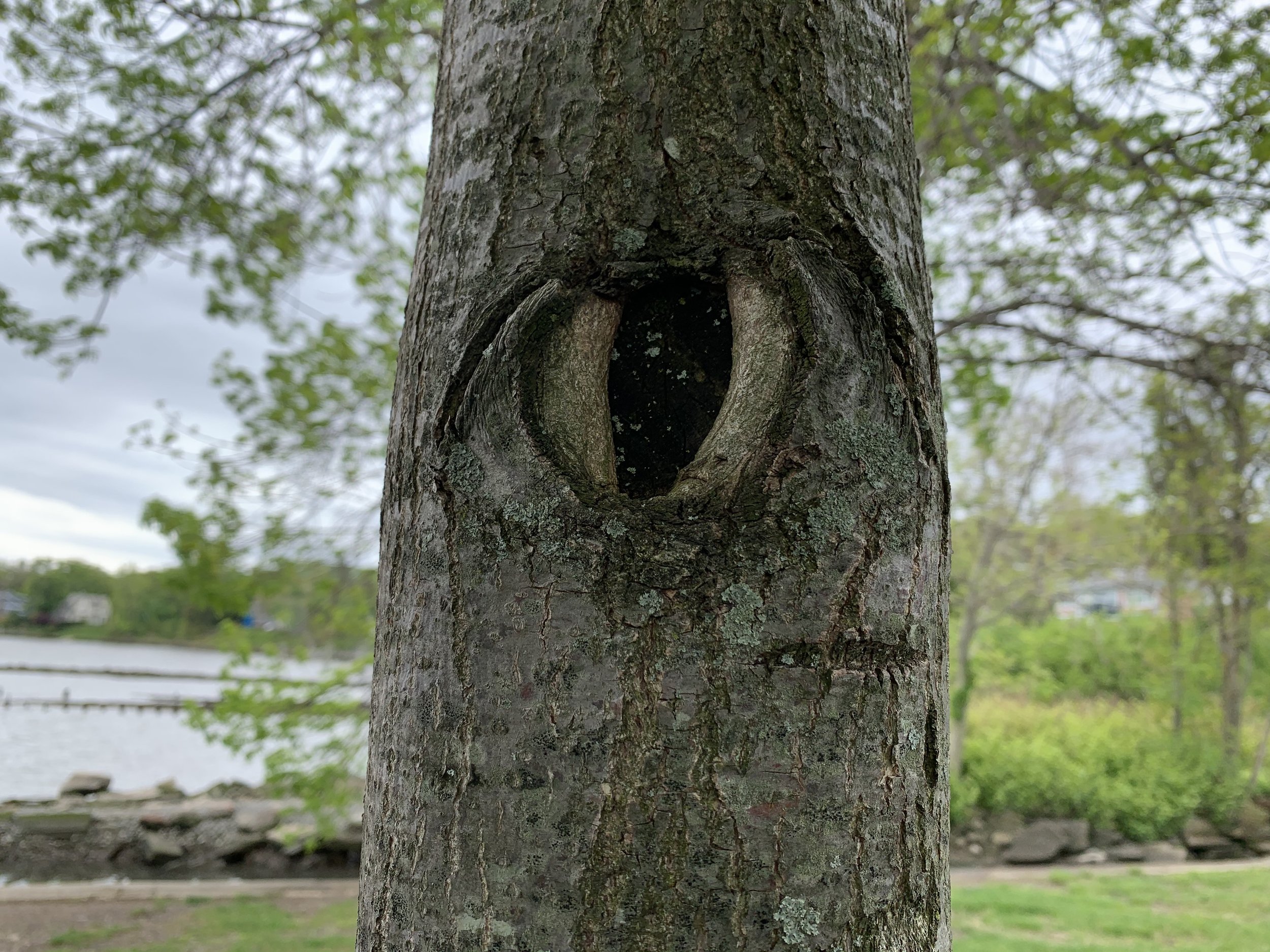

hudson valley, ny 2021

hudson valley, ny 2020

new york, ny, 2022

collage, 2006

Beyond Bear Mountain, the Catskills, the Palisades, what may be the defining feature of the lower Hudson River Valley, where was raised and spent the past year of my adult life, is the river itself. The river flows south from Lake Tear in the Clouds in the Adirondack Mountains for its 315-mile course, nourishing over 200 species of fish and even, as rumor would have it, whales (one such rare sighting may have inspired Melville’s Moby Dick). The deepest point of the river is just over 200 feet, known as “World’s End,” and is found near the United States Military Academy, which feels fitting.

The Hudson continues its southward flow to find its widest point (3.5 miles) at Haverstraw Bay, then continues to the end of New York State’s boundary with New Jersey, wrapping around the largest city in the United States like its nothing, then trails off into the Atlantic Ocean. Almost 9,000 miles of freshwater streams and rivers make up the Lower Hudson River Watershed and its tributary system: over 300 lakes, reservoirs, and ponds.

The river is kind of a big deal.

Since the sea level in the region rises enough to flood the basin, the Hudson Valley is called a drowned river valley, and to be more specific, the river is actually an estuary, a mix of salt and freshwater due to the tidal push from the Atlantic, which makes for a strong mix of river currents.

One way to describe the river is versatile, diverse, a bounty; another is vulnerable. Because of the Hudson’s precarious position between all this human activity, the river succumbs to our most common environmental problems, most famously in the 1970’s when General Electric dumped mass amounts of PCBs, an extremely toxic chemical, into the river that disrupted the natural ecology and the people who lived on the river. For my whole life, I’ve noticed the water’s aliveness, that my relationship to the river was tied to the health of the region. I knew that water was a vital resource. The Hudson and its tributaries felt like my own veins.

A fish suffocating in water sounds like a contradiction, but as of July 6th of this year, thousands of Atlantic menhaden, a coastal fish, suffocated along the Hudson River between the New York Harbor and Haverstraw Bay. The river is out of balance. Hypoxia is the official term, a word describing when the oxygen level of an organic environment decreases to a deadly level. This can happen in a water body, such as the Hudson, but also in our own. Anoxia occurs when there is no oxygen left.

I read several articles on the death of these fish, and found a reporter who lists the cause of fish death as “death by climate change,” which may be a more frequently used term than I am aware of, but the phrase catches me off guard. This feels like a necessary clarification, a straight shot. Because oyster beds and reefs are lost from prolonged heat and lack of rain, because sewage has led to an increase in nutrients in the water and filter feeder populations have declined, algae has spurred in growth, sucking up the oxygen, creating these dead zones.

I want to know more about these fish so I can mourn them. I learn things that make me, as a vegan, happy: they’re too small and oily to eat. Then, another article gives me pause: they are often harvested to be turned into fertilizer. The same fertilizer that might leak into the river and cause these dead zones. My brain loops. I want different facts. I want different histories.

When we are lost there is still a choice in what we are losing. I think of what has felt ripped away from me in life, moments where I believed I had anything but a choice in their departure: romantic relationships ending, perceived failure of dreams, my father’s death, a precious sketchbook left on a bus containing years of drawings and writings. Though different scales of loss, in these moments I wanted anything but to be told I had a choice, that any power remained. I felt more immediate relief in believing that loss meant an end, plain and simple. An end was unjust. An end I could rile against, even surrender my power to. There was nothing to discover in an end but the fact of my pain.

Growing up in the Hudson Valley, my friends and I celebrated storms. There is a quiet magic to the Hudson Valley in the hours before a storm. You can feel the heaviness of the sky. The river’s waves grow, hurry. Gull calls freckle the wind. I thought of this particular sort of delight a few years ago when I was living across the country, far from home, listening to Brandi Carlilse’s “The Eye” for the first time. She sings: “You can dance in a hurricane / But only if you're standing in the eye.” The song felt like a lesson in art making, in living. It reminded me of our wisdom as children as we stomped through puddles, ruined clothes in rainwater dancing, sprinting home as the seconds between lightning and thunder drew dangerously close together.

Several catastrophic storms hit Nyack throughout my adolescence and young adulthood: Hurricane Floyd, Hurricane Sandy, and dozens of severe thunderstorms that flooded the streets, enough so I remember seeing a local paddle along the newly formed Main Street tributary in their kayak. The wild storms of my youth were simply an occasion for the delight of walking headfirst into danger, but doing so with an internal resolve that you will survive, that you will be changed through your bravery. We were bold, riotous. We were learning to endure.

At the time I don’t imagine we were fully conscious of the measurable harm brought on by these storms: the economic damage, the lives lost, the isolation. Eventually, we’d heed our parents’ warnings and come back inside despite our yearning for our bodies to be the landing spot for the heavy rain.

Nyack sits on the widest point of the Hudson River, an anomaly of a river whose currents run both ways, what the indigenous people originally named “Muhheakunnuk” (Great Waters Constantly in Motion). Despite learning to sail on the river, and spending more time capsized, fearing the eels I felt on occasion circle my ankles as I struggled to pull myself back on board, I eventually became fearful of the river. I worried I’d been submerged in poison when I learned of General Electric dumping over a million pounds of PCBs into the Hudson from 1947-1977, the evidence of which is still found in the sediment of the river, the fish, us.

Still, I would occasionally take a friend’s dare to sneak onto the private pier at the end of my block and jump off. Whoever went first inspired the other. There are reasons this was foolish: splintery shards of dock under the water surface, the river’s notoriously strong current, but we must’ve known we were affirming the knowledge of our bodies, the symbolism of going right towards your fear. I think this is why when we return as adults to walk our childhood streets, we still sneak onto the pier, trudging along the rocks, knowing fully well that we could’ve simply come at an earlier hour to be let in.

rockland county, ny, 2017

I finished Lily King’s new novel, Writers and Lovers, the other night. The book follows a young women as she moves into adulthood and takes authority over her life, which means she began to choose new things. It’s one of those books that feel like a palette cleanser after what for me was a long spell of struggling to finish books, a phase that when I’m inside of it makes me feel like a phony (a writer who can’t read?!!?). The stress of the pandemic mashed with a hyper-productive end of summer/early fall where I felt everything in my life decided to happen at once: three big work projects, my film projects getting picked up for screenings and speaking engagements, new teaching assignments, a last minute move, and the general muddle of changing seasons, but this time during a political upheaval and the loss of a lifelong friendship as a consequence of this. Prose was simply difficult for me to get into. Poetry I could do. I returned to my usual favorites, reading Ross Gay’s new poetry collection, Be Holding, which I pre-ordered a long while back and was delightfully surprised by when it finally arrived in the mail. I attended some Rutgers folks’ readings: Patrick Rosal, Micaiah Johnson, Paul Lisicky, poetry readings at the Brooklyn Book Festival, at Provincetown, a series (Good Words) held by my dear friends Katie Willingham and Lauren Prastien. I wanted to hear others read, to hear poems, but I avoided long pages of text, what I claimed to love. I watched well written TV (The Good Lord Bird, Forever, and Pose), and comedy (Difficult People, the new season of PEN15, reruns of The Mindy Project as always). I did my weekly virtual classes with my yoga studio, met my writing group, practiced guitar with an old friend, and doodled. I tried to focus on the stacks of novels I wanted to read, but didn’t.

“You don't realize how much effort you've put into covering things up until you try to dig them out,” King’s narrator Casey observes. I envied Casey’s clarity in naming her desire to write. To write, specifically, a book. I’ve struggled for years to say that I want that for myself: a book. I resist the idea of becoming a product, to write a book just to have one like many writers seem to do. I want to connect through my work, to share my stories with an audience, and having a book feels like a portal to do so. Still, I fill with fear over what that might do to me. I’ve always been happy (comfortable?) with writing singular stories and essays, chiseling away for years on manuscripts, script after script, typed pages from notebooks to be saved as PDFs on my desktop, racking up hundreds of magazine rejections a year with a few quiet yeses in between. I didn’t imagine myself having a book despite actively working on its parts. Reading Casey’s emotional journey to publish her own, I felt myself open up.

Like me, Casey starts the book un-partnered, without a full-time job with benefits and stability, in a city she’s known her whole life, unsure if she wants to have children or marry. Many of my friends who are writers or artists seem to know these things about themselves, have acted on at least one of them, and have those as roots on which to lean when the writing life seems as precarious as it’s always been.

I’ve often dated partners who were more realized than me as artists, working in their field as a professional, playing weekly shows, whatever it was, they were doing it. Things were happening. For me, I found caverns for myself within their dreams, quiet moments in a recording studio watching a partner record in which I could start a new story, hiding away in another partner’s basement studio while he worked a night shift to work on my novel, and the office of another partner’s hotel room to edit scripts while he worked on film sets. As much as I called myself a feminist, an independent artist, it was so easy to make my wanting smaller inside of another’s. I hid. I didn’t fully risk.

“Nearly every guy I've dated believed they should already be famous, believed that greatness was their destiny and they were already behind schedule. An early moment of intimacy often involved a confession of this sort: a childhood, teacher's prophecy, a genius IQ. At first, with my boyfriend in college, I believed it, too. Later, I thought I was just choosing delusional men. Now I understand it's how boys are raised to think, how they are lured into adulthood. I've met ambitious women, driven women, but no woman has ever told me that greatness was her destiny,” King writes, and I cry.

There were years when the only “help” I got was from men, many of whom were raised to see greatness as their destiny, some of whom turned out to be manipulating me, stealing my work and ideas or labor for their own gain, or expecting our relationship to become sexual, others who called me on my bullshit. But it wasn’t only gender—it was also my fear. “All problems with writing and performing come from fear. Fear of exposure, fear of weakness, fear of lack of talent, fear of looking like a fool for trying, for even thinking you could write in the first place. It's all fear. If we didn't have fear, imagine the creativity in the world. Fear holds us back every step of the way.” This past year, I’ve challenged myself to walk through much of my fear. Before the pandemic, I spent 8 months in the basement of a jazz club every Saturday studying with an acting coach. I performed and co-directed a new short film. I took personal and professional plunges, but they ground to a halt when lockdown began. Like many, my life felt frozen. I felt I regressed, quieted my desires again, just wanted to make it through the day.

Even with all of these leaps, and leaps back, even before the pandemic, I still struggled to say one simple thing: I want to write a book. Books. I want you to hold my books. I want you to read my characters and to love them the way I have, the way they’ve seen me through years and years of discovery. I long for Casey’s ending, “There’s a particular feeling in your body when something goes right after a long time of things going wrong. It feels warm and sweet and loose.” I want what I write to loosen something up in you, to make you face your fear, too.

Where have you been?

Away from you

I felt you being gone

But how could you?

Everything I do is to return to you

Am I how you measure time?

Love is our best measure

You’ve been hard to reach

I felt you being gone

Everything I do is to return to you

Where have you been?

Away from you

But how could you?

Am I how you measure time?

Love is our best measure

You’ve been hard to reach

westchester county, ny, 2020

rockland county, ny, 2020

To carry, to hold, to stand against

a flag pole with claws and pull down

the cub from where she crawled

after being chased from garbage pails

in comparison to the Momma I saw

at the zoo with her face smooshed to

grass like the wild one she is

making the most of her time here,

which isn’t unlike me as I walk past

her den and hope she doesn’t hear

my carless steps crunching by her

den, which is another word for home,

which is another word for what is private,

what is left untamed, unknown, untethered

to meaning, but can hold many at once

these meanings, and me, and the bear,

and her cubs,

two.

rockland county, ny, 2020

rockland county, ny, 2020

I think it’s just this, from Philip Levine’s “The Lesson”: “What was to come? you ask. This world / as we have it, utterly knowable, / utterly unacceptable, utterly unlovable, / the world we waken to each day”

“Besides, your death isn’t specific to a place, not at all, you’re dead everywhere. So that, basically, I realize that it isn’t wanting to escape, not at all, it’s combating wanting to stay, because I would stay, I’ll always want to come back, that’s very clear, I think, that’s what I’m deciding, that it’s precisely that distance, that tension, that sustains me. That desire towards that other thing. If I have it, I succumb. If I stay here, I succumb. I know that. Maybe, then, my doubts these past days have been nothing other than to succumb or not to succumb,” confesses Emilia, the protagonist in Romina Paula’s August (her first novel to be translated into English), to her friend who has passed away.

Emilia doesn’t know what she wants. She recently returned to her home city to mourn her friend, to spread her ashes, to runaway, she thinks, from a different life, or perhaps to return more fully to it. She isn’t sure, but the novel to me is about naming and reframing the desire to escape. The illusory nature of escape is presented most clearly as she moves between the life she’s chosen (Buenos Aires) and the one she was born into (her home).

But life is always present. She’s already in her life. There is no place to go that is not her life.